Some events in our life stand out like none others–so disorienting that they challenge us to know where we are and maybe who we are.

I had one of those events this week:

I set myself on fire.

It wasn’t hard to do. I was fixing my husband Steve a special supper the evening before he was scheduled for hip surgery. Not needing to be glamorous (I was hoping to paint that night), I was wearing one of Steve’s old flannel shirts, with its sleeves ripped off at the elbows that I called my painting shirt. I could wear it without worrying about bits of acrylic paint or globs of acrylic gloss medium dropping on it by mistake.

Dinner was fresh corn and broiled salmon. At the prescribed time to flip the salmon, I bent over and a thread from my shirt must have touched the open flame under the corn. The thread caught fire, and I saw a small flame on my sleeve.

I immediately tried to pat it out. But instead of being extinguished, the flame jumped. I patted it again, and the fire spread until four-inch flames covered the front of the shirt. I ran to the sink, but the water did not put them out. Then I really got it: I was on fire.

Images flew before me of Vietnamese monks immolating themselves and witches being set on fire. Is this how burning one’s self up begins? Not like you ever want to set yourself on fire, but my timing was awful. How could I go off-island to an Emergency Room (ER) with Steve needing to leave pre-dawn for his long-awaited surgery? My brain started spinning.

Fortunately, Steve was a few yards away and rushed to my side. With his know-what-to-do steadiness, he pulled the burning flannel shirt over my head and slammed it in the sink, where the flames soon went out.

I stood at the counter trembling, not daring to look at my arm or body, while images of enormous flames darting from my chest filled my mind. To help ease the trauma and increase my chances of healing, I started “tapping” using EFT (emotional freedom technique), and drumming lightly on my face and chest with my fingers. Steve looked at me quizzically, but I said, “trauma,” and he understood. By the end of ten minutes, my mind had relaxed enough to allow me to function, and I was able to think of something besides flames engulfing me.

Steve helped doctor the wound with a burn salve and gauze. He said the damage didn’t look too bad, and we both hoped I would escape the incident with only a minor burn.

The whole event felt surreal, like time-out-of-time, so sudden, disorienting, and out of context that it had no place in the typical construct I call “an evening in my life.”

It was a moment I would never forget.

Around 2 a.m. that night after some fitful sleep, I realized what had happened: the acrylic residue on my shirt must have accelerated and fed the fire.

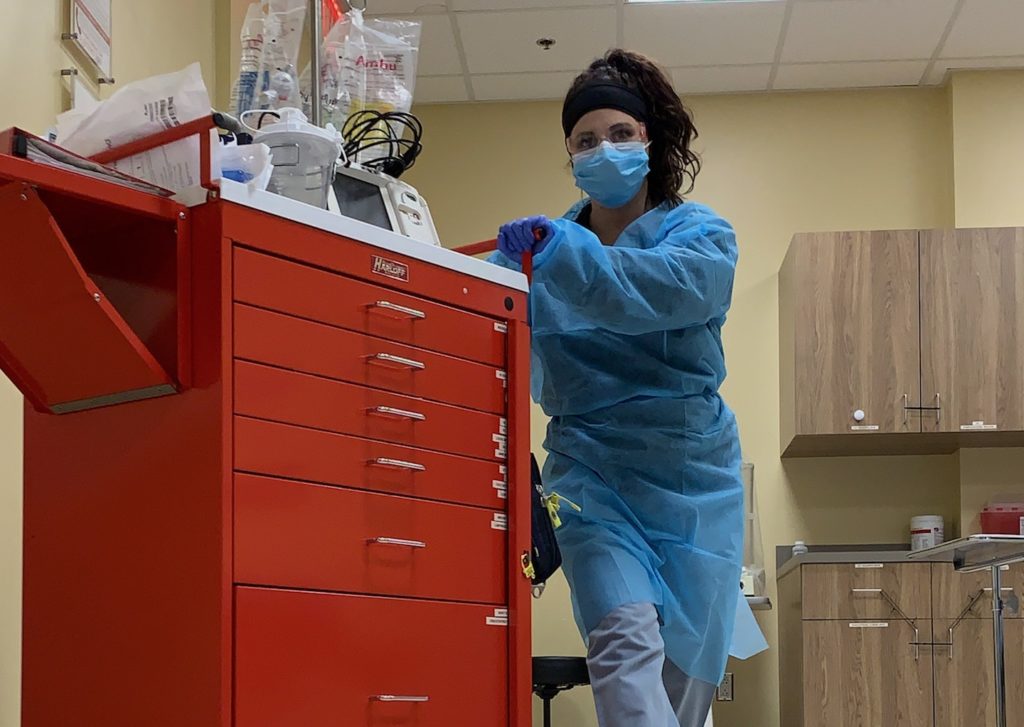

Fortunately, the next day, Steve could still go to his planned hip replacement surgery. Despite my fears about possible worst-case scenarios, everything went well, and his operation and treatment provided an example of modern medicine at its best. I was glad and relieved. Because it doesn’t always go that well in the hospital.

Hospital ERs are rife with moments when time moves out of time and life seems to stop.

Being admitted to an ER or waiting with a loved one is like entering an alien world. Life looms large. Many people are disoriented, lights blink, sounds beep, and gurneys travel back and forth. The rooms smell like medicine, antiseptic, and fear. Anxiety lives palpably in the air, full of questions like, “What’s happening?”, “How did I get here?” “Where am I?” “When do I leave?” and “Will I (or he/she/they) live?”

I remember sitting with Steve in the ER a few years ago, gazing idly at the clock, knowing how powerless I was to control time. It was as if a giant “now” consumed the space, and all thoughts of the future had to be put on hold.

The idea that we can “control our lives” looked increasingly illusory.

That’s the way it is in a moment.

Returning home

On my way home on the ferry after Steve’s successful surgery, I had time to reflect on the power of moments.

During the immediacy of a terrifying incident, such as a trip to the ER or my fire experience, there’s no place to figure out “what it means.”

Moments are experiences that come without lessons, morale, or meaning. They just are, and they consume all of our attention.

Later we may make up meanings or create a lesson or story about an event. Obviously, one lesson from my fire experience could be, “Be careful of loose threads around flames,” or “Acrylic paints and fire don’t mix.”

While useful teachings, such lessons don’t begin to touch the enormity of the experience.

Moments like mine can lead us to wonder and, in my case, gratitude, and we may tune in more to the beauty and mystery of the world around us. As I stared at the Seattle skyline and churning waters behind the ferry, the world looked brighter and more beautiful, including the colorful containers stacked in the Seattle shipyard, the purple mountains in the distance, and the white waves dancing across indigo waters.

By some miracle, I survived the fire with only a minor burn around one elbow, like a sunburn that scalded away a layer of skin. I was so lucky.

I’m not going to end this post by trying to wrap a bow around my experience or tell you what it meant.

It was too big for that.

Sometimes we just need to honor the magnitude of moments by stepping away from the stories we tell about our lives and standing in the power of now, if only for an instant.

5 Responses

Oh my, Sally! When I read the title of this, I did not actually think you set yourself on fire. Thank goodness all is well!

Yes indeed. Thanks for your good wishes!

Sally, I love this post. Especially the end when you say, “I will not try to wrap a bow around my experience or tell you what it meant“, bravo bravo! It simply was as it was. The gift is you created art from it, this beautiful post to share the journey. Now that is meaningful!

We also are thankful you are doing okay! I for one treasure having you for a friend!

Thank you so much!