Uncontrolled anger kills. Combined with political motives and manipulation it starts wars. It’s challenging not to be angry and scared by Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

Yet, I don’t want to forget that anger, with its heat, can also be used to create art.

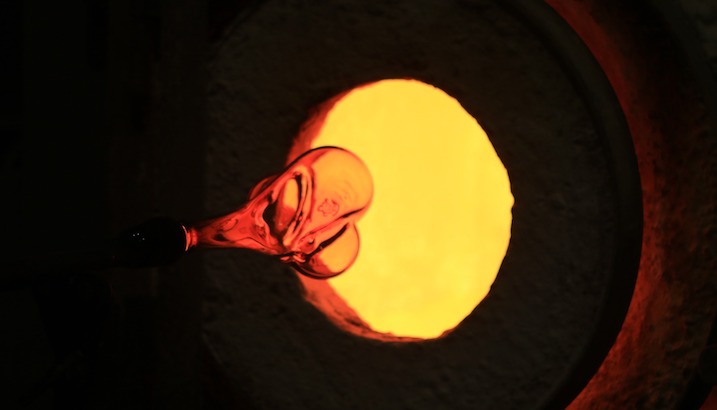

At the Tacoma Art Museum, glassblowers demonstrate the art of glassmaking in the Museum’s hotshop amphitheater. Craftspeople move glass in and out of kilns whose temperatures exceed 1500 degrees Fahrenheit, shaping pieces with expert care. The glassmakers work in teams, moving like dancers whose moves have been skillfully choreographed so that no one gets hurt.

They know how to use the danger and power of enormous heat to create works of beauty.

Glassblowing is a metaphor for how anger, when used carefully, can fuel our creativity, help us create beauty, and support social change. I’m studying how to transform anger into creative fuel for an online class I teach in March for Chicago’s Infinity Foundation. (Confession: I teach what I need to know.)

I’m not comfortable with anger. When I feel it bubbling inside of me or surfacing in a confrontation, my first reaction is to want to back away. My brain’s emotional reactivity center offers me the option of fight/flight/freeze and in work settings, I usually freeze. I go numb, try to make myself invisible, or retreat into my invisible protective emotional tortoiseshell. My next step is to try to fly away.

But I need my anger, we all do. It’s a form of energy. Channeled into constructive directions, anger can fill us with passion and lifeforce. Suppressing it saps our energy and leads to myriad health problems, that can range from autoimmune conditions to anxiety, eating disorders to poor cancer recovery rates, and much more.

To live healthily and creatively, we need to tap into our anger, while learning to manage its destructive sides.

Anger’s two faces

Two vividly different faces of how to use anger stand out to me. In the one represented in the video below of social commentator Bill O’Reilly, we watch him lashing out at his producer. Whether you hate or love O’Reilly’s politics is irrelevant here, the video illustrates uncontrolled anger, explosive and vitriolic. (Cleanse your palette after watching it with the beautiful Jon Batiste rendition of “Blackbird” below.)

The O’Reilly meltdown is almost comical, but not if you, as many of us, have suffered trauma or abuse at the hands of an authority figure, in which case it could be retriggering. Many of us carry wounds caused by uncontrolled or repressed anger, which can make O’Reilly’s full-frontal attack difficult to watch.

Without self-reflection, we may not notice the pre-made bonfires we carry within that are just waiting for a spark from an external situation to light our internal tinder. We explode not just because of the situation at hand but because of past pain.

To constructively channel our anger, we have to first recognize the piles of tinder we are already carrying.

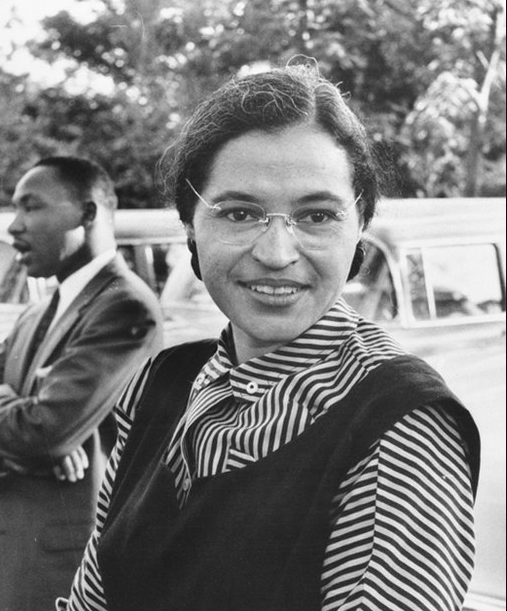

A different face of anger lives in the stories about Rosa Parks.

When I was growing up, I heard a sanitized version of the Rosa Parks story, her anger stripped from the narrative. What I learned in school sounded like “Poor black girl, exhausted from working, decides one day that she’s too tired to go to the back of the bus.” Nobody told me that Parks was ANGRY and had been working for social justice for a long time before refusing to give up her seat. (She worked as an activist for the rest of her life.)

Maybe it was strategic, at that point in history, to let the media focus on her being sad rather than mad. Our culture tolerates, “sad, poor, tired black woman” better than the “feisty, raging, black woman” (aka bitch). Parks had trained in social action at Tennessee’s Highlander Folk School; she had learned how to use her anger deliberately and wisely.

Her action was not a result of being tired after a long day. She wrote in her autobiography, “I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Rosa Parks was a woman who understood strategy and timing, and, like our glassblowers, knew how to be careful. (Click here for more facts on Rosa Parks)

How our anger and our reactions to it is shaped by gender and race

Our society views and reacts to anger differently depending on who has power. For a white man, showing anger can be seen as a sign of strength. A woman showing her anger (except, perhaps, in defense of her kids) may be shunned as a whiner, difficult, unfeminine, ugly, or a nag. An angry black woman can be seen as dangerous. If you’re angry and a black man, you’re at double risk of being seen as dangerous and criminal. In her brilliant book, Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger, Soraya Chemaly offers research illustrating how gender and race influence our reactions to anger.

I wish our culture was beyond gender stereotypes, but the data suggest otherwise. I remember the misogynist social media feeding frenzy when Hilary Clinton was running for President and was accused of being an aggressive, raving, lying, crazy, bitch–and worse. As a seasoned international diplomat and skilled politician, she knew how to artfully control her anger. Yet any anger she voiced made national news and was used to confirm the stereotypes.

Her action was not a result of being tired after a long day. She wrote in her autobiography, “I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Rosa Parks was a woman who understood strategy and timing, and, like our glassblowers, knew how to be careful. (Click here for more facts on Rosa Parks)

We all need our anger

How can you see what’s happening in the world today and not be at least a little angry?

Reading Chemaly’s book, I felt anger learning how women are still being asked to swallow theirs. Women need to be able to express themselves, loudly and clearly. We all do.

Chemaly closes her book writing:

Anger is the demand of accountability. It is evaluation, judgment, and refutation. It is reflective, visionary, and participatory. It’s a speech act, a social statement, an intention, and a purpose. It’s a risk and a threat. A confirmation and a wish. It is both powerlessness and power, palliative and a provocation. In anger, you will find both ferocity and comfort, vulnerability and hurt. Anger is the expression of hope. How much anger is too much? Certainly not the anger that, for many of us, is a remembering of a self we learned to hide and quiet.

It is willful and disobedient. It is survival, liberation, creativity, urgency, and vibrancy. It is a statement of need. ..If it is poison, it is also the antidote.

Anger can give us the fuel we need to create as long as we don’t let it burn us up. We can learn to work with the hot kiln to shape beauty.

We can:

- Deactivate our reactive amygdala.

- Stay embodied, present to what is happening within us.

- Acknowledge where the past might be coloring perceptions of the present.

- Reflect and strive to understand the situations that spark our anger.

- Channel ouranger towards constructive change including creative, artistic, and inspired heartwork as well as social activism.

For information about my class on “Using Anger as Creative Fuel” click here.

Next week, I’ll write about how to do that. In the meantime, I’ll pray for peace.

But now, for a moment of respite, here’s Jon Batiste.

2 Responses

Hi Sally,

Sharing something about “Blackbird” that I’m amazed to learn!

From a Facebook friend:

“Are you familiar with the song “Blackbird” by The Beatles? Most of us are. I had no idea the meaning behind it. Did you? I will never listen to it the same way again.

“Paul McCartney was visiting America. It is said that he was sitting, resting, when he heard a woman screaming. He looked up to see a black woman being surrounded by the police. The police had her handcuffed, and were beating her. He thought the woman had committed a terrible crime. He found out “the crime” she committed was to sit in a section reserved for whites.

Paul was shocked. There was no segregation in England. But, here in America, the land of freedom, this is how blacks were being treated. McCartney and the Beatles went back home to England, but he would remember what he saw, how he felt, the unfairness of it all.

He also remembered watching television and following the news in America, the race riots and what was happening in Little Rock, Arkansas, what was going on in the Civil Rights movement. He saw the picture of 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford attempt to attend classes at Little Rock Central High School as an angry mob followed her, yelling, “Drag her over this tree! Let’s take care of that n**ger!'” and “Lynch her! Lynch her!” “No n**ger b*tch is going to get in our school!”

McCartney couldn’t believe this was happening in America. He thought of these women being mistreated, simply because of the color of her skin. He sat down and started writing.

Last year at a concert, he would meet two of the women who inspired him to write one of his most memorable songs, Thelma Mothershed Wair and Elizabeth Eckford, members of the Little Rock Nine (pictured here).

McCartney would tell the audience he was inspired by the courage of these women: “Way back in the Sixties, there was a lot of trouble going on over civil rights, particularly in Little Rock. We would notice this on the news back in England, so it’s a really important place for us, because to me, this is where civil rights started. We would see what was going on and sympathize with the people going through those troubles, and it made me want to write a song that, if it ever got back to the people going through those troubles, it might just help them a little bit, and that’s this next one.”

He explained that when he started writing the song, he had in mind a black woman, but in England, “girls” were referred to as “birds.” And, so the song started:

“Blackbird singing in the dead of night

Take these broken wings and learn to fly

All your life

You were only waiting

for this moment to arise.”

McCartney added that he and the Beatles cared passionately about the Civil Rights movement, “so this was really a song from me to a black woman, experiencing these problems in the States: ‘Let me encourage you to keep trying, to keep your faith, there is hope.’ ”

“Blackbird singing in the dead of night

Take these sunken eyes and learn to see

All your life

You were only waiting

for this moment to be free.”

Thanks so much for sharing this story. I had no idea and it certainly adds a depth when I think about the song. I think Jon Batiste captures it, too.