What’s in a map?

What’s in a map?

Is it a literal representation of a territory? Or a way of seeing that guides us into a relationship with the place, object or process being described?

Maps don’t have to be literal to be accurate.

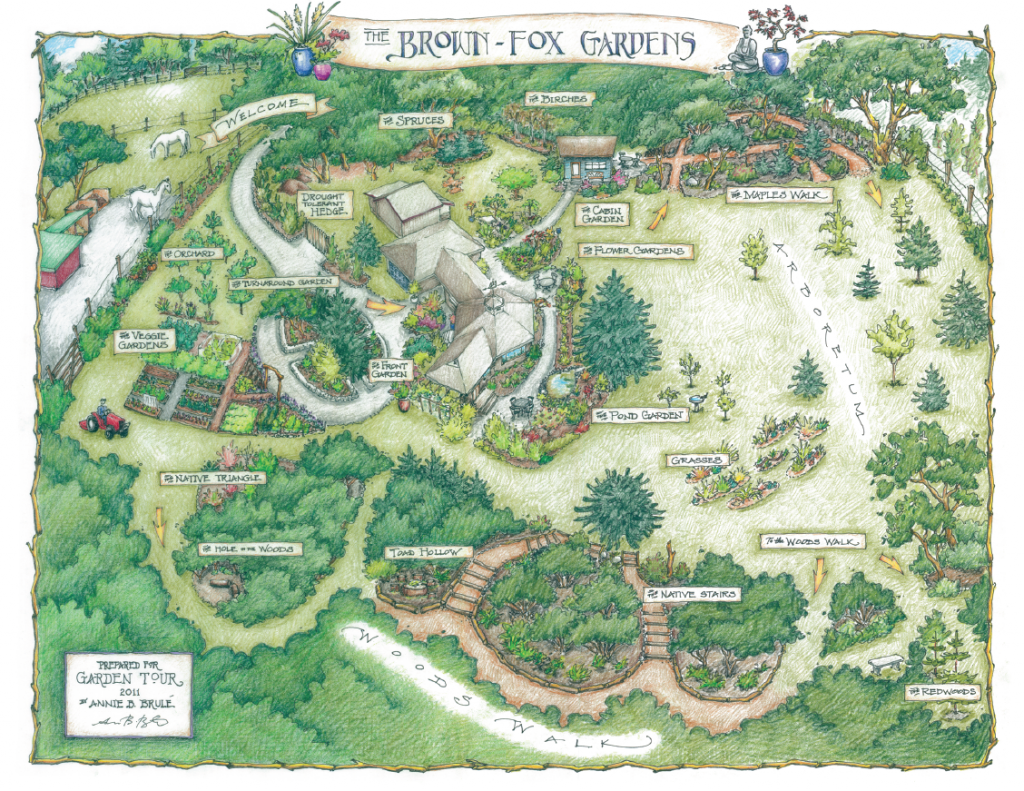

The photo above is a map of my garden done several years ago by graphic illustrator and map-maker Annie Brulé. Several years ago, anticipating the hundreds of people who would be visiting our place for a big garden tour, my husband and I commissioned a map from Annie. We wanted one that would suggest a route they could follow while introducing them to the spirit of the place.

We had a map, an aerial photo of the house and garden, which gave us a literal picture of the space. It was useless.

Viewing the aerial was like staring at a maze of data without having a key to understand it.

We could have drawn a simple black and white route to follow – but that option also didn’t look interesting.

Annie’s map, however captured the feel of our garden, and although it was full of whimsy (on the day of the tour, one woman liked it so much that she wanted a copy of our “hobbit map” she could frame), it was also something people used to navigate around our many garden beds.

Annie captured important details (check if you can find my husband Steve on his tractor) and left out a lot. She was an artist, including and excluding details, choosing how to frame, and where to focus attention.

Her map did what leaders do: frame a situation and focus people’s attention.

As leaders, we all frame with our vision. We frame with our mindsets, our attitudes, the details we choose to see and the ones we deny.

Different frames lead us to completely different pictures, and completely different futures.

Do we look at the Islamic world through the frame of terrorism or through the frame of the poet, Rumi?

Storytellers know the power of framing. My storytelling colleague Michael Margolis teaches that the art of creating a business story starts with finding the right frame.

Before Annie creates a map, she engages with the place she will be mapping. She asks questions and confirms purpose. She engages her mind and her senses. She takes photographs and listens to those who know the place. And then she quietly walks by herself, letting the place speak to her.

“I walk around a site, until I feel confident that I can fly over it in my mind.”

When Annie began her design work for us, we walked the property together. Seeing it through her eyes, the land came alive in new ways. There was a flow to our gardens, a magic that I had always felt but never seen depicted.

When Annie presented us with her map, we cried. She had gotten it.

Her map honored our land.

Map-makers have tremendous power hidden within the choices they make. They can describe a world ripe for exploitation or an eco-system full of connections. They can document a reality pointing to a bleak environmental future or map the small and specific steps communities are taking towards a different outcome.

Check out the maps Annie has made for several of the Northwest Tribes. In mapping their gardens, their traditional foods, and the eco-systems of forests and Puget Sound that the tribes rely on for food, Annie was able to honor old ways with new eyes.

Maps can help us see the future.

And maps, done like Annie’s, can bring us hope.

Plus, it’s so cool to gaze at a map of our hobbit paradise during those long rainy winter nights when we can’t garden.

Want more thoughts about mapping – or how those of us who aren’t illustrators can create our own maps? Read on to see Annie’s words from an interview I did with her earlier this year.

Interview between Annie Brule and Sally Fox: On the Power of Maps

AB: We tend to take maps for granted – a lot of people just think of maps as the thing that lives on their phone that you pull up to navigate with ….but there’s a whole other world out there – that I got drawn into…and that’s the metaphorical world of maps.

Our minds often work in a map-like way – we talk about mapping out our plans and our schedules.

That kind of mapping and envisioning can also be done in that graphic vocabulary we think of as ‘I’m going to read a map’.

My work falls between literal mapping and metaphorical mapping, which is a more whimsical and visioning type of mapping.

SF: How do you prepare yourself when you’re going to make a map and you see all these things in front of you, far more than you could ever record? Do you go into a kind of zone?

AB Some people would say that I’m always in that zone!!! (she laughs).

I ask a lot of questions and the most important are: “What is this map for? And who is it for? Who’s going to be looking at it? And what do they need to understand about this place?”

The second part of the process is that zone that you talked about.

I walk around a site, until I feel confident that I can fly over it in my mind. It’s like dreaming – because it involves flying and imagination. You have to know a place well before you can map it in the way that I map. It’s very personal and very human scale mapping.

SF: That’s such an interesting combination: you talk about flying, dreaming and walking all at the same time – as if you’re operating in different realities – seeing in so many different dimensions.

Has the process of becoming map-maker changed you?

AB: Absolutely

When I walk into any space, urban or rural I tend to go into that zone…that wasn’t part of my experience even five or ten years ago. It certainly affects the way I experience spaces as a whole

Especially in the city. The way that I experience urban spaces is much more connected than if I weren’t doing this kind of work. When I walk into a square, I immediately take a survey of how many alleys are connected to it and which streets are going by…and which colors are predominant.

SF: You have a sensitivity to see connections, and eco-systems as well as colors.

Do you ever see a map when you think of your life?

AB: Absolutely.

Some of the most fruitful exercises I tend to do right around this time of year [New Year’s] is mapping the future. A friend gave me a wonderful assignment a few years back when I was going through a whole series of life transitions….

“Draw a map of your own future.”

I went straight home and started that assignment. It wasn’t anything grand – it’s not a big colorful art project I could put on the wall – it’s mostly taken place in notebooks and sketchbooks with ballpoint pens.

But it’s absolutely fascinating. Because you can shift your point of view –that’s a little like flying – you can stand in the present and look forward.

Or, you can stand in the future and pretend you’re looking back – and think about what you want to be looking back on.

You can play with time and geography in those interesting, malleable ways and that’s another very personal way of mapping.

SF: You can look from different angles. It sounds like you can shift your future by shifting your perspective and that mapping allows you to do all that.

AB: It’s a beautiful ally… to bring graphics into the service of envisioning what’s next in your life and self-transformation.![]()

SF: If someone wanted to experiment with mapping, how would they start? Even if they didn’t have your artistic skills…

AB: I’d say explore the use of creative icons.

Most people can glance at the most common icons used in maps and go, “Yeah I get that.” Icons are easy to come up with and don’t have to look good. They just have to be a simple symbol that means something to you: stars, spirals, circles, flowers – they could be anything. Stick figures can work just as well, as something more involved, probably even better than a more detailed drawing when you’re mapping out relationships between things, and ideas, people.

If you wanted to look for some of those creative icons, there’s a beautiful resource call Greenmap, an ecologically focused coalition of citizen mapmakers. They have beautiful icon sets, developed collaboratively, a universal set of icons that transcend language.

SF – If you had a book to recommend?

AB – Catherine Harmon’s book You Are Here. She’s got a great book that opens your mind to the many ways maps can be used.

AB – Catherine Harmon’s book You Are Here. She’s got a great book that opens your mind to the many ways maps can be used.

SF: You have an interesting set of clients, including some of the Northwest tribes. Is there a sense of calling behind the work you are choosing?

AB: Maps have allowed very disparate callings, which I once thought were at odds with each other, to come together. [I grew up with] a huge appreciation for the natural world and life systems and the way humans fit in to those ecosystems. A large part of my twenties was devoted to environmental activism – and that was often time taken away from illustration projects. [Before mapping] I couldn’t find a way to stitch my life together….[I was split between] the political campaigns or time in the studio.

Over the years, I realized that maps are essentially a tool for framing the world.

We live in a world where there are competing frameworks.

A couple of examples: natural resources as resources for exploitation by humans

or

a framework where humans are but one small part of a giant web of life – not better than any other beings.

Those two frameworks are clashing mightily these days. And both of those ways of viewing the world will make wildly different maps.

Maps can be very informative about where a group or a nation is coming from. Maps can be a political tool, a tool of extraction, exploration, colonization, reclamation, resurgence of cultural traditions.

Like any piece of art, the map is a reflection of the one who made it or the group or the nation.

SF: How are maps a tool for restoring hope?

AB: They can be amazing that way. And the most hopeful maps are those at the local level because the problems on the horizon are so extensive and so intricate.

When you take the big view, it’s hard to remain hopeful. But when you take that look down at the human scale: the scale of a city, a town, a bioregion, you can start to look at: yes, streams where salmon no longer come; yes, environmental degradation sites; but you can also look at resurgences of local food systems, you can map places where there weren’t urban garden five years [and there are now.]

It all comes down to how your frame it. I certainly could paint a hopeful picture of a particular neighborhood in Seattle and turn around the next day and create a very depressing map

It’s all in the emphasis and the framing.

The projects that have given me the most hope and are intended to inspire people to even more self-possessed awareness, action, and engagement in their own governance and future, are the ones that map garden projects and food projects.

Some for the tribes have involved local food systems [where] there is a renaissance in traditional food culture tied to the ecosystem. The tribes have a heritage of living very directly from the land, and harvesting from Puget Sound and the forests, where human health is tied to the health of the ecosystems. Of course, all of our health is tied to the health of ecosystems but indigenous peoples often experience that much more directly.

See Annie’s map of the Northwest Indian Treatment Center Healing Gardens and the Muckleshoot Traditional Food Map.

SF: It’s a community where you’re offering a piece of hope that’s very reality based – the relationship between the food, the education, the culture, and the way forward –a real gift.

For more about Annie’s work see Brule illustration.com