Do you remember hearing, “sticks and stones will break my bones but words will never hurt me?” Maybe your Mom, like mine, was trying to comfort you when you were eight and being bullied.

Do you remember hearing, “sticks and stones will break my bones but words will never hurt me?” Maybe your Mom, like mine, was trying to comfort you when you were eight and being bullied.

Trouble is, she was wrong.

Words, through false labels, do more than hurt – they can even kill.

Accusatory labels broadcast on the radio in Rwanda incited unimaginable genocide. They appealed to people who wanted to know that they could have the world be the way they wanted to be – if only they followed the promised path.

Calling someone “handicapped,” “demented,” “homo,” “corrupt,” or other terms for difference, separates us from each other and protects us from acknowledging the fear or anxieties we carry within ourselves. We reduce a world of complex colors into black and white. Labels create a kind of certainty – so we have someone to blame for the things about life that we don’t want to face.

But even if they’re flawed, once labels stick, they’re hard to remove.

What to do when you’re labeled

Imagine your political opponent throws an unfair label at you. Sure you can ask them to recant, take back what they said, just like a judge can tell a jury to ignore something.

Trouble is, there’s a language grenade lying in the space the moment it is spoken.

What if the other candidate accuses you:

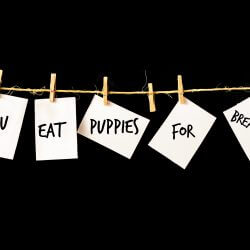

“You’re the kind of person who eats puppies for breakfast.”

You respond that he’s lying, it’s absurd, and there’s no evidence. You tell him to take it back and he says:

“I don’t have to prove that you eat puppies for breakfast. I didn’t say you ate puppies for breakfast – I just said you’re the kind of person who eats puppies for breakfast. Because everyone I’ve ever known who has brown hair and blue eyes like you eats puppies for breakfast. And it’s a very bad thing to eat puppies for breakfast. And if you weren’t guilty of eating puppies for breakfast, you wouldn’t be upset about me saying that you ate puppies for breakfast.”

Oh the magic of repetition! What phrase will you remember? The press loves it, because they have their headline:

“Candidate accuses opponent of eating puppies for breakfast.” And you thought you could talk about the issues!

Linguistically this is a crafty move. Emotionally infused sound bites stick in our imaginations.

How to respond:

Your (not very good) options:

- Ignore it (knowing the phrase is now the new elephant in the room).

- Ask for evidence (which already acknowledges something that is absurd – and who listens to evidence these days?)

- Accuse your accuser of being a lier (which will cause some to confirm your guilt).

- Throw back a label of your own (thus descending to the same level of discourse).

- Try to shift the discussion back to substantive issues. (Good luck getting anyone’s attention with this!)

- Argue that the situation is more complex than what a label can portray. (Same problem).

- Have a rant with your BFF. (Useful – but the elephant is still in the room).

- Look inside yourself to see why you’re so upset. (Similarly useful – and now the public may think you’re a wimp).

- Write a blog about it (a truly winning idea!)

Bad news: I don’t have the answer. What would you do?

I’m searching because what I see in public discourse today deeply troubles me.

Certainty comforts

We’re in a world that’s terribly complex – and that can be hard to handle.

One of the reasons people label is that labels offer the hope of more certainty in a complicated world – we’re right, they’re wrong and they’ve created the problems and changes we’re having difficulty embracing. Change can be scary, certainty comforting.

Maybe we need to find ways to celebrate uncertainty.

To find the positive power in uncertainty, I decided to look for a moment for those who have learned to embrace uncertainty in science, philosophy and art.

Science

Physicist Sean Carroll writes:

“We have to be willing to accept uncertainty and incomplete knowledge, and always be ready to update our beliefs as new evidence comes in…”

Scientists ask questions, challenge assumptions, and stay open to new data. (Imagine that!)

Philosophy.

Alan Watts in his famous book The Wisdom of Insecurity writes:

“There is a contradiction in wanting to be perfectly secure in a universe whose very nature is momentariness and fluidity. But the contradiction lies a little deeper than the mere conflict between the desire for security and the fact of change. If I want to be secure, that is, protected from the flux of life, I am wanting to be separate from life. Yet it is this very sense of separateness which makes me feel insecure…”

Thus our quest for security and certainty leaves us feeling even more insecure.

Art

In accepting the Nobel Prize, Saul Bellow offered these remarks:

“Only art penetrates what pride, passion, intelligence and habit erect on all sides — the seeming realities of this world. There is another reality, the genuine one, which we lose sight of. This other reality is always sending us hints, which without art, we can’t receive.”

In other words, we need artists to challenge our certainty about what we call reality.

(Thanks to Maria Popova of www.brainpickings.org for the above references.)

Labels give us a seductive shorthand.

Simple black and white answers are powerful, because they offer us false comfort when the circumstances we face demand real inquiry – not labels.

When we throw simple, judgmental labels at life, we lose the magic of inquiry and opportunity to ponder complexity. And we lose our chance to perceive, if only for a moment, what is beautiful, ineffable, essential, and impossible to box in.

And now back to you for your thoughts.

P.S. Inspiration for this blog came from a recent YES Magazine column written by veteran journalist Bill Buzenberg – a tireless advocate for the role of the media in supporting an informed public.

4 Responses

Not too long ago, I saw a quote that said something like: “if you repeat a lie often enough, people will believe it. And, if you keep saying it, at some point you will believe it yourself.” The quote is from Hitler’s Mein Komfp.

I don’t repeat this often, but to your point, the lies, the labeling, the lack of respect for facts and truth, the lack of integrity regarding Truth is, for me, scary. And dangerous. For me, the best antedote to bullying, is continuing to speak about the vision, about inspiring hope, about believing in what’s good and possible, and continueing to call on our better selves, the parts of us wherein lie our hearts and our souls and our curiosity and our compassion. Not having an answer may be the best resolution right now. Because if there is no right answer, maybe we will each step up to taking on the responsibility for being accountable for what we say.

Thanks Sandra, That’s a terrifying quote we all need to hear these days! I appreciate your points!

Hi Sally,

I always love your thoughtful pieces. To ” I don’t have the answer. What would you do?” My answer is humor, a fierce weapon if ever there was one, perhaps with a touch of sarcasm. Spontaneous laughter when someone throws out a false accusation shifts the energy pretty quickly. “I’d tell you to get your facts straight but you don’t appear to have any. Perhaps you could get someone to help you”. It can take the stick from the bully. -Jeff

This doesn’t speak to your main point about why we feel the need to categorize people as “the other,” but rather to the list of strategies for responding to name-calling.

Do you remember the “cookies” kerfluffle when George H.W. Bush was running against Bill Clinton, and Bush criticized Hillary’s comment about “I could have stayed home baking cookies…”?

It was an unfair criticism, because Bush and the others omitted the following sentence, in which Hillary said that feminism meant the right of women to do as they wish, whether to stay home or have a career.

But Bill Clinton responded to Bush’s comment by putting it in a different light. He said, “You’d think he[Bush] was running for first lady.”

Suddenly, Bush looked like a laughing stock, not Hillary or Bill.

Let’s suppose, then, that your real disagreement with the person who said “You are the kind of person who eats puppies for breakfast” is his(her?) support of drone attacks in Syria. You might reply with something like, “Would you rather have someone who eats puppies or someone who kills hundreds of them by bombing the houses they live in?”

Or suppose that your basic disagreement is about education funding. Then you might try this:

“I don’t know what puppies taste like. But I’m more concerned with giving our children the kind of education that will let them grow up to be successful adults who can afford to give their children a breakfast that’s both healthy and delicious!”

Or this:

“Instead of talking about how to make sure that every child has a chance to make something of herself, (s)he’d rather talk about breakfast foods!”

This strategy is about showing the name-calling to be an attempt to divert attention from the real issues, in a (perhaps) humorous way.