Saying “joy” and “dementia” in one sentence could sound like an oxymoron.

Like many, I have a fear that I might someday lose part of my mind.

Dementia’s not a far fetched concern: the stats on its occurrence rise significantly for every year we pass eighty.

Being with dementia can be tough for both patients and families. I’ve seen it up close. My brilliant scientist uncle was reduced by Alzheimer’s to being like a little boy. A favorite cousin spent half her life worrying that she might die from early-onset dementia, as had her Mom. She did.

And yet, heartbreak is not the whole story about dementia.

What may be almost as difficult as living with dementia is living within the narrative society has created.

We fixate on what people with dementia have lost, rather than the capacities they still have.

Patients and their families may feel ashamed by the condition as if it’s something to hide. It’s tempting to want to tuck patients away, where their deficiencies won’t disturb anyone.

Dementia is stigmatized.

My recent podcast guests, Mary Fridley and Susan Massad, of the Eastside Institute in New York City, call this dementia story “the tragedy narrative.”

This outdated story keeps us from exploring the possibilities for development, joy, and relationship that dementia has not taken away.

Mary and Susan are offering us a new narrative, using the vehicle of improvisational theatre to help us look at dementia in new ways.

The lenses we use shape what we see

Susan, retired from a fifty-year career as an MD, says that when you look at dementia through a medical lens, what you see is an individual problem that medicine can’t fix. The medical model sees deterioration and offers no hope.

But that’s not the only lens through which dementia can be viewed.

If we look through a social-relational lens, dementia is not just a problem for the patient. It’s a condition that affects many, including family, doctors, caregivers, and friends. Susan and Mary refer to this community affected by dementia as the “dementia ensemble,” a reference to the world of performance they know well.

Yes, dementia can take away memory and some mental powers.

Yet life is about much more than brain-powered activity. It’s also about laughing, loving, using our imaginations, being social, creating, and enjoying music, art. and nature. When we only see brain decline, we miss seeing the range of capacities people with dementia still have.

Towards a more humane outlook

Even if you don’t know anyone with dementia, it’s important to notice the idea, implicit in the tragedy narrative, that one needs to be fully-functioning, cognitively, to be a complete human being. Brains are good; they’re just not all of what makes us human.

No one, whatever their brain capacity, deserves to be written off.

When we devalue a group of people, we devalue ourselves, making what it is to be human that much smaller.

In our brain-oriented, success-driven, results-oriented world, some categories of people can be seen as incomplete, inferior, or even not necessary, including people with:

- Dementia

- Developmental disabilities, like Down’s Syndrome

- Brain Injuries

- Parkinsons and other degenerative conditions that can affect how we think and function*

No wonder we try to tuck such people away, where they can be taken care of without being seen or honored.

*(When we start thinking this way, the list rapidly expands to include older people, people with other differences, crazy owners of Springer Spaniels, etc.)

Using improvisational theatre to bring a more life-filled approach to the dementia community

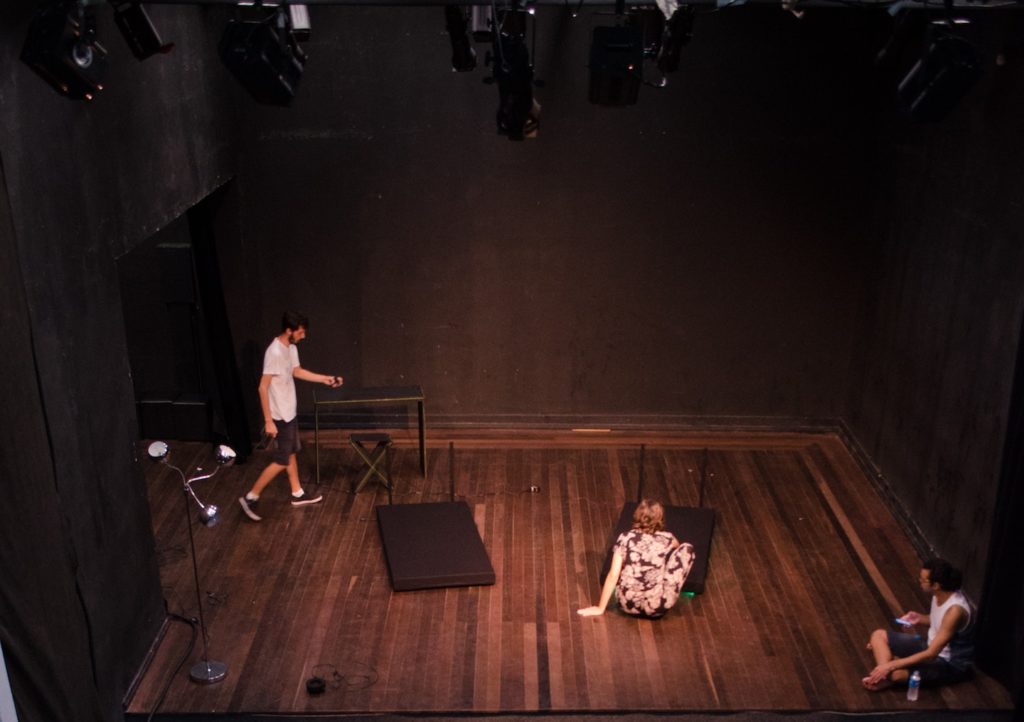

Mary and Susan run improv theatre groups in which the dementia ensemble, the community of people affected by dementia, are invited to play together, without consideration of their cognitive capabilities. Patients play with caregivers, family, and others. Improv opens up a way for everyone to connect, laugh, and have fun.

The key to improv lives in two magic words, “Yes/and.” For dementia patients, who hear a constant barrage of “No, that’s not true,” and “No, you can’t do that or say that,” it can be tremendously positive to hear the word, “Yes.” In improv you affirm and say yes to any “offer” your partner makes (such as a “The moon is looking purple tonight”), however fantastical it might sound. As an improv player, your job is to empower your partner. (“Yes, it’s purple, and I see a big green halo around it.”)

When my mother’s mind was deteriorating with old-age dementia, she talked a lot about “going home.” Talking “sense” to her was useless. It worked far better to play a bit, asking, “When are you leaving Mom?” and “Who will be there?” “What are you looking forward to doing?” Saying “No” to her stopped the conversation. Saying “yes/and” kept the connection going.

(I know “Yes/and” doesn’t apply to all situations, but it sure helps change the culture of “No, but” that can surround dementia patients.)

All the world’s a stage

As faculty at the Eastside Institute, Mary and Susan are skilled in social therapeutics, “an approach to human development and social change that relates to people of all ages and life circumstances as social performers and creators of their lives.”

Like actors performing together on the stage of life.

In a great play, like Shakespeare’s, not all roles require speaking. An actor may stand on stage, saying barely a word, but you still know her presence is important to the scene. The actor playing the fool often has a key role.

In life, as in stage performance, many roles are possible, including valuable roles played by people affected by dementia.

I still pray that I won’t lose parts of my mind. It hurt to see my cousin Brenda’s decline. Yet when I was with her, I loved her smile, kindness towards others, imagination, love of family, and how she kept making art,up until the end of her life.

She would have loved to do improv. I think she would have been great at it.

If I acquire dementia, I will be comforted if the people around me know that I am still here, that I still matter, that I enjoy laughing, dancing and making art, and that my presence has a purpose, even if that purpose lies beyond the realm of what any of us can understand.

PS You can hear the podcast interview this post was drawn from over on the Vital Presence podcast. Click here to listen.

4 Responses

As I continue to lose memory of names important to me, and rely more and more on my cell phone calendar to keep up with scheduled activities, I’ll try to keep this blog in mind. It’s inspiring and comforting

Thanks

Sally, I love your perspective! This really helps with my dear aunt who is losing her mind but opening her heart.